EPA’s temporary suspension of environmental enforcement seems to have reduced pollution reporting

SkyTruth intern Dhiya Sathananthan detected a drop in pollution reporting that might be linked to EPA’s temporary reporting suspension in 2020.

On March 26, 2020 the U.S.Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced a temporary suspension in the enforcement of environmental legal obligations across a broad spectrum of activities. While EPA indicated that entities should make every effort to meet their environmental compliance obligations, the suspension granted a free pass in cases where compliance was not “reasonably practicable” due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In effect, there would be no penalty and no accountability for failing to report pollution events or comply with environmental standards. Environmental groups expressed serious concerns about the EPA’s decision, with Natural Resource Defense Council CEO Gina McCarthy describing it as an “open license to pollute. Plain and simple.”

At SkyTruth, we feared an increase in environmental pollution might occur as a result of this policy. We also feared industries might fail to report pollution events if they were not required to do so, thereby masking any increase in pollution. Luckily, the policy was only in effect for a few months before ending on August 31, 2020. Nevertheless, we wanted to see what impact this temporary policy could have had on pollution reporting to the U.S. Coast Guard’s National Response Center (NRC). Initially an avenue for reporting oil spills, the NRC is now the designated point of contact for reporting accidental oil, chemical, radiological, and etiological discharge into the environment across the U.S.

SkyTruth has developed one of the largest and most comprehensive databases of U.S. pollution reports from the NRC, which we make freely available to anyone through SkyTruth Alerts, our environmental monitoring platform. With generous support from the Clif Family Foundation, SkyTruth analyzed the NRC reports and tracked whether reporting declined in this period of federal leniency, from March 13, 2020 to August 31, 2020.

As a SkyTruth intern, I jumped at the chance to work on this project as I really wanted to increase my experience analyzing large datasets. I analyzed NRC reports from 2010 to 2021; around 260,000 reports total (after cleaning the dataset to remove duplicates and alerts that did not geo-tag correctly). Using the Pandas software library for python, I got to work making sense of this huge dataset by breaking it into manageable chunks. I first filtered out railway and other vehicle-related incidents because the policy change didn’t apply to them. Such incidents make up a significant part of the dataset, and so removing them was an important step in reducing the noise in the data to help me identify trends. I then graphed the total number of reports by month over time. As Image 1 shows, the peak in the middle of 2020 is slightly narrower than the years before and after, indicating that the temporary easement may have affected the pollution reporting in this time.

Image 1. The total number of pollution reports to the NRC per month, from January 2010 to December 2021. The section in red represents the months during which the temporary policy was active.

Comparing the total number of reports in the date range in which the easement was active (March 13 to August 31) over multiple years shows that 2020 had the lowest number of reports in the years 2012 to 2021 (Image 2). In addition, the highest year to year variation occurs between 2019 and 2020 (decrease of 15%), and subsequently between 2020 and 2021 (increase of 15%), ignoring the anomalous numbers in 2010 and 2011. Given the high variation in this dataset it is hard to predict how many pollution reports could be expected in the easement period in 2020 without the policy change, and therefore difficult to estimate the impact of the change on the of number of reports. A close approximation can perhaps be made by taking the average number of the reports in this same period in the years before (2019) and after (2021). Using this metric, one would expect 10,900 reports in the period March 13 to August 31, 2020. This means that the EPA’s policy has allowed 1508 pollution events (or 14%) to go unreported.

Image 2. Number of reports between March 13 and August 31 every year between 2012 – 2021. EPA’s easement policy occurred in 2020. Data is sourced from NRC pollution reporting database from January 2010 to December 2021.

Next, I looked at the medium affected – whether the pollution event affected land, water, air, soil, or is unknown – as shown in Image 3. Most incidents are related to the water sector, making up 60% of the reports. This means that there was discharge into water bodies that could have originated either from land or from vessels. The second most commonly affected medium is land, followed by air. In addition, 6.7% of pollution reports are categorized as affecting unknown media, and the smallest fraction (3%) affecting soil. This trend is consistent both during and outside of the months of the policy easement.

Image 3. Medium affected by pollution events, shown as a percent of the total reports in the time period. Data is sourced from NRC pollution reporting database January 2010 to December 2021.

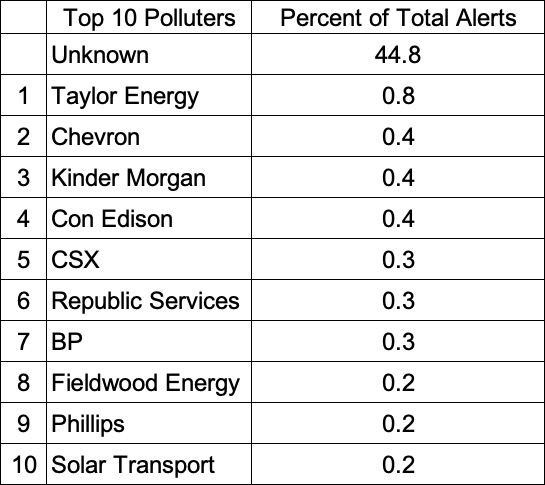

I also tracked the industries listed as ‘suspected responsible party’ for the pollution event. Table 1 shows a list of the top 10 suspected responsible parties for pollution events from January, 2012 – December, 2021. A large chunk of the reports (45%) are not linked to any suspected responsible party, and even the company suspected to be responsible for the largest number of pollution incidents only makes up 0.8% of the total reports. In other words, pollution events are not caused by a handful of bad actors, but rather are dispersed among many sources.

It is most likely that the reports with an unknown responsible party are those made by passers-by. In other words, we estimate that 55% of pollution reports are from industries self-reporting while the other 45% are made by concerned citizens. Unfortunately, the public versions of NRC reports don’t offer information on who submits each pollution report, so we can’t be certain of this, or draw any conclusions about how the policy change might have affected who is reporting pollution events. This trend of approximately 45% of reports having an unknown ‘suspected responsible party’ holds true during the months of the easement as well as outside of those months. This would indicate that those reporting the pollution events did not change as a result of the easement policy. However, as mentioned before, we can’t be sure of this as informers aren’t identified in the NRC reports.

The exact ranking of the top (suspected) polluters varies slightly during the months of the easement, but this is likely normal variation and not a direct result of the policy change. It should be noted that reports from 2010 and 2011 were excluded from this analysis as the number of reports in these years is much lower compared to subsequent years and therefore don’t reflect current trends.

Table 1. The top 10 (suspected) responsible parties for environmental pollution events from January, 2012 to December, 2021 based on the NRC pollution reporting database.

The NRC database also fails to include much detail about the severity of pollution events. Therefore, this analysis does not speak to the severity of pollution during and outside of the easement policy. While I was able to analyze the quantitative data, I would have liked access to more qualitative data that could have illuminated more effects of the policy change that are not obvious from just looking at the number and frequency of pollution reports. For example, some kind of severity scale, perhaps a measure of the area affected, might have provided additional information about any differences in the easement timeframe.

Given the information available, it seems that the EPA’s temporary policy can be linked to a 14% reduction in pollution reporting in the period from March 13 to August 31 2020, assuming that the real number of pollution events were similar to the years before and after. It is also possible that the real number is higher than estimated, if the policy change encouraged a more lax attitude towards pollution. Fourteen percent is therefore a conservative estimate of how many pollution events went unreported in this time. We at SkyTruth are glad this temporary policy change was short lived. I am grateful to the staff at the NRC for their hard work in collecting and maintaining this large dataset, and I hope the system can be improved in the future to provide more detailed, qualitative data that can make an important system even more informative.