The trouble with methane

Methane leaks from oil and gas operations are a big problem for climate. Solutions are coming.

Methane is an odorless, colorless gas. It’s a very simple chemical — an atom of carbon surrounded by four atoms of hydrogen. Lighter than air, it’s the main component of natural gas, targeted by drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking) operations around the world. It also commonly flows into wells that are producing crude oil. In the early days of oil drilling, methane was considered a dangerous nuisance, highly flammable and prone to exploding. The easiest way to deal with it was to separate the gas from the oil, divert it away from the well, and intentionally burn if off: a process known as flaring. [See our global flaring maps here.]

Over the 162 years since the world’s first commercial oil well was drilled in Pennsylvania, a vast network of oil and gas wells, pipelines, pumping stations, storage tanks, refineries, and distribution lines has been built. And this network — including the modern pieces — is riddled with leaks. Methane escapes from wellheads, from oil/gas separators, from compressor stations, and from pipeline valves. These so-called “fugitive emissions” are only part of the story. Some operators get rid of unwanted methane by intentionally venting it directly into the air, a practice that is illegal in most cases but difficult to detect.

And that’s a big problem, because methane in the air absorbs heat from the sun, warming up our atmosphere. And although it doesn’t last as long as the more familiar climate villain, carbon dioxide, it’s up to 86 times more effective at trapping the sun’s heat. That means the leaks and intentional venting of methane from oil and gas operations is turbocharging climate change, greatly accelerating global warming and the human suffering that results.

What’s the solution? In the long term, ramping down our use of oil and natural gas. In the short term, fixing these leaks — IF we can figure out exactly where they are, in the vast web of oil and gas infrastructure. The good news is, the technology for finding these leaks has been rapidly improving.

On the ground, there are a few interesting techniques for remotely detecting methane leaks and venting. One of the most eye-catching is the use of Foward-Looking Infrared (FLIR) cameras, which have thermal infrared detectors that are tuned to match the spectral characteristics of methane, other hydrocarbons, and volatile organic compounds. When trained on a methane leak, FLIR cameras produce ghostly images and videos that illustrate the flow of methane into the air. Our partners at Earthworks have captured hundreds of examples of leaks and direct venting from oil and gas fields and facilities, including this example (image below) of an unlit flare stack spewing methane that’s undetectable to the human eye.

A variety of hand-held leak detectors feature infrared lasers instead of camera systems, but use the same principle of detecting the spectral properties of methane and other gases, and offer the potential for measuring the concentration of gas in the leak. Other manufacturers, such as Picarro, build sensors that draw in a sample of air and directly measure the concentration of methane.

Those air-sampling sensors can also be used from low-flying aircraft to map the plumes of methane being emitted from oil and gas facilities down below. The Environmental Defense Fund took to the air to create PermianMap, an in-depth look at the methane venting problem plaguing the world’s most productive oil field, the Permian Basin straddling Texas and New Mexico. They found dozens of examples of unlit flare stacks venting methane, and estimated one in 10 flares was unlit or burning inefficiently — wasting enough methane to power two million homes in the US.

It’s not practical, or safe, to fly methane-hunting helicopters continuously around all of the oil and gas fields on Earth. So, what can we do at scale, using the global view from space?

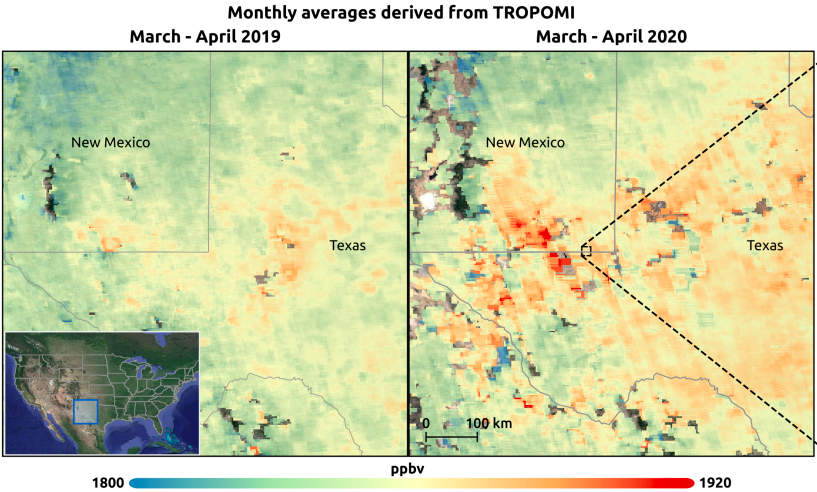

The European Space Agency’s Copernicus program launched the first Sentinel-5 satellite in 2017, carrying an instrument called the Tropospheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) capable of measuring the concentrations of methane and other pollutants in the air. This system has been used to show much greater amounts of methane coming from oil and gas operations throughout the Permian Basin than expected. TROPOMI operates at a relatively coarse level of detail, not generally able to pinpoint the sources of methane leaks except in exceptional cases.

Atmospheric methane concentration measured using TROPOMI over the Permian Basin oil field, comparing 2019 (left) to 2020 (right). See below for detail from the inset box shown on the Texas-New Mexico border. Images courtesy European Space Agency.

But good news is coming on that front. Commercial companies like GHGSat and Bluefield are launching satellites capable of detecting leaks with pinpoint accuracy, offering oil and gas companies their services to help target repair and maintenance activities. And with the expected launch in late 2022 of MethaneSAT, even conservation organizations are rolling up their sleeves and getting into the space business. A project of the Environmental Defense Fund, MethaneSat will be capable of detecting smaller leaks than GHGsat over a broader area with each overflight, albeit with less spatial precision.

Someday, watchdogs will be able to use the free, public data from MethaneSAT to discover problems with leaking methane, then following up with GHGSat or similar commercial systems to pinpoint the locations of those leaks. Once we know where they are, we can identify the companies responsible for this climate-altering waste of natural gas, creating public pressure on industry and governments to fix those damaging leaks.

Detail from the inset box shown in previous figure: methane plume detected by GHGSat superimposed on recent high-resolution aerial imagery linking this plume to a specific drilling site. Image courtesy European Space Agency.

To stave off the worst effects of runaway global warming, this capability can’t come too soon.