The Marcellus Shale Natural Gas Boom in Wetzel County, West Virginia

Today’s post is by guest blogger Jim Sheehan, a GIS and remote-sensing specialist and PhD student at West Virginia University.

—

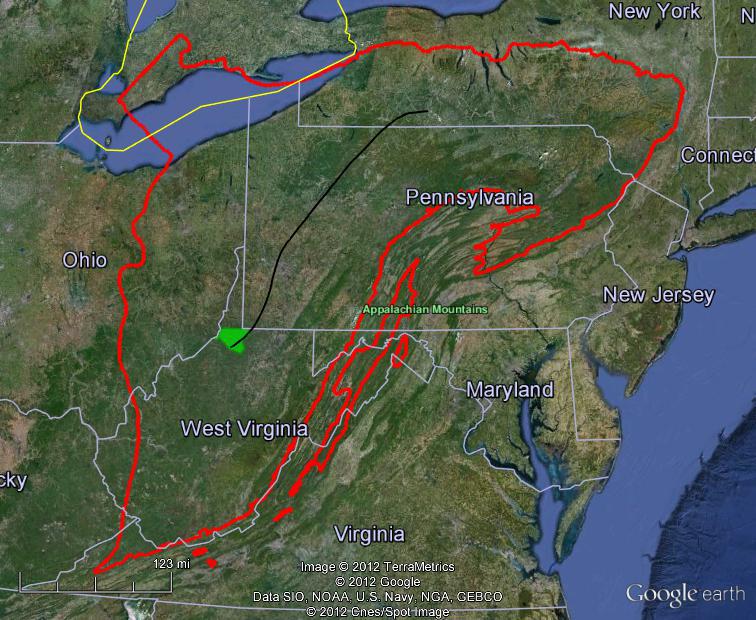

Many of you are likely aware of the huge push to drill the Marcellus Shale for its abundant natural gas. You may have seen it for yourself, or been exposed to the many advertisements on TV, radio, and in print. Development of this new, unconventional source of energy, underlying a large expanse of the eastern US (Fig. 1), has exploded just in the past few years.

Fig. 1. The red line shows the Marcellus Shale extent (drawn from USGS report) and the black line represents the wet-dry gas boundary (drawn from Penn State Marcellus Center for Outreach and Research map). Wetzel County is the filled green shape.

Industry-sponsored ads* commonly tout that drilling the Marcellus will decrease our reliance on foreign energy, create jobs and stimulate the economy, and have a lighter environmental footprint than other types of energy development. However, behind much of the industry’s full-court press is the highly controversial hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) process involved in Marcellus gas extraction, and other concerns such as the disturbances to local communities. Still, despite the issues, Marcellus drilling is unlikely to slow down anytime soon due to its value to the gas companies and those leasing their access rights at the very least.

*For more information about the energy industry advertising, here is a very revealing article by FAIR’s (Fairness & Accuracy In Reporting) Miranda Spencer:

Natural Gas and the News – Most messages on fracking ‘brought to you by our sponsors

A new ridge top Marcellus drill pad in Wetzel Co. in a formerly forested lot. The drilling has ceased for the moment as the well apparently is being vented (photo: Jim Sheehan).

I often notice something about the pictures in the ads that conflicts with the nature of Marcellus drilling in some areas: the activity is often shown in a pastoral setting. Indeed, much of the industry does operate in rural areas dominated by agriculture. However, now that the price of natural gas has plummeted, the industry is increasingly focused on the more valuable “wet gas” region (approximately west of the black line in Fig. 1), which drops down into Wetzel County in northern West Virginia. Much of Wetzel Co. is forest, and as such exemplifies some of the best that “Wild and Wonderful” West Virginia has to offer. I believe this forest has particularly high value, ecologically and for other reasons, and may be vulnerable to this type of disturbance.

With the help of SkyTruth, who kindly provided me some blog space and encouragement, here I explore the recent development of Marcellus (and other unconventional drilling) in Wetzel Co. To show the increase in drilling I used well information and geographic coordinates for 102 completed unconventional wells in Wetzel Co. from 2007-2011 that I obtained from the West Virginia Geological & Economic Survey’s “Pipeline-Plus” database.

According to Pipeline-Plus, most of the 102 wells drilled target the Marcellus formation (75 as of 2011), but I also included wells that drill other Devonian Period formations. I did this after zooming in on all the well sites in Google Earth and finding they share a scale of activity (large pads for example) different from the conventional oil and gas drilling long a part of this region. It turns out the other Devonian Period formations can also hold high-value natural gas (wet gas or super-rich gas*)

*Gas containing hydrocarbon compounds such as ethane, propane, and butane in addition to methane.

Next, I zoom in to Wetzel Co. (Fig. 2) for greater on-the-ground detail. The 102 wells actually occur on about 50 separate pads, since multiple directional wells can be drilled per pad. A great feature of Google Earth is that you can view current and historical aerial and satellite images to explore change through time. Particularly valuable to me are the 2011 (current), 2009, and 2007 leaf-on aerial photographs from the National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP). Using the sequence of these images, I often see in great detail the land cover prior to preparation and drilling of the well site, characteristics of the well pad and the activity, and any associated infrastructure development (roads, pipelines, and holding ponds).

Fig. 2. Wetzel Co. and 2007-11 well locations (red = Marcellus, pink = other Devonian Period formations), and proposed/in progress wells 2011-present (as of September, 2012; dark gray dots). Also shown are the Lewis Wetzel Wildlife Management Area (green outline) and two of its forested headwater streams (light blue), and the Fishing Creek streams (dark blue) that flow into the Ohio River near New Martinsville, WV.

I’ve only begun to examine each well site and map the pad and any infrastructure, but here is an example of how large and problematic an impact can be. In Fig. 2, much activity is concentrated in the Lewis Wetzel Wildlife Management Area (green outline). While the state owns the surface, most of the subsurface rights are privately owned. Because the area is public, it’s easy to directly observe the activity (within reason!), which I’ve done since 2008. Wyatt Run (Fig. 3 and the upper light blue stream in Fig. 2) is one of the area’s forested headwater streams that in particular interests me, since it was one of the most pristine but now has been degraded by new activity. The integrity of headwater streams is crucial to downstream water quality, so I’ve included in Fig. 3 Wyatt’s connection to Fishing Creek, which in turn flows to the Ohio River.

Fig. 3. A side view of Wyatt Run at the Lewis Wetzel WMA, with a new Marcellus pad, holding pond, and access road as of 2011. The pad (and a new 2012 pad not captured by the photo) has “slipped” due to the steep topography characteristic of the region.

The side of the ridge top well pad visible in Fig. 3, and a new one I’ve marked that occurred after the 2011 NAIP aerial, have “slipped” substantially due to the steep, rather unstable terrain, and are causing heavily sedimentation in Wyatt Run. There are efforts to correct the problem, but unfortunately it appears to be difficult to stop the erosion. As of September 2012 the sedimentation continues, and there have even been substantial direct impacts to the stream itself. Clearly, better planning is needed during the siting of well pads to avoid situations like this, and the amount of activity, at least in this watershed, appears to be at odds with industry claims of a light environmental footprint.

Left: a mudslide coming down from the 2012 Marcellus ridge top pad that has “slipped” above Wyatt Run. Right: a downstream pool of Wyatt Run continually polluted by the heavy sedimentation from the ridge top pads. (photos: Jim Sheehan)

I’ll also use this location to illustrate another concern. With new pads comes much associated infrastructure that can fragment previously continuous forest, and potentially have a negative effect on wildlife that prefer large, undisturbed forest patches. While some wildlife may benefit, new roads and pipelines can also act as corridors – bringing in undesirable or exotic plants and animals. The drilling and site preparation also result in noise and air pollution. I can say first-hand that recreation (hunting, wildlife viewing, etc.) is much reduced in the formerly popular Lewis Wetzel Wildlife Management Area, and heavy vehicle traffic and the dust and potholes it brings seriously disturb the local community.

In closing, given the rapid increase in drilling between 2007-2011 and the amount of post-2011 proposed/in-progress wells I’ve begun to map (Fig. 2), it is clear that the impacts to the forests of Wetzel Co. can happen very quickly. The next NAIP aerial should happen in 2013, and provide a new, detailed snapshot of drilling-related activity. In the meantime, I wish to use what we can now see to increase awareness of environmental costs seldom heard about, and make them an important consideration in the development of this energy resource.

Jim Sheehan, October 7, 2012

Morgantown, WV